Nick Black VP LPG of Argus Media in conversation with Makoto Arahata

Makoto Arahata has been a source of wisdom and expertise about Japan’s LP Gas sector for many years as the leading light of the Japan LP Gas Association — and a key presence at World LP Gas Association Forums and meetings.

He has over 40 years experience of the LP Gas industry in Japan, witnessing the birth and growth of what was an entirely new industry when he started out. Now retired from the Association, Arahata-san has recently set up a new firm Arahata LPG Consulting, based in Tokyo, aiming to remain an invaluable resource of LP Gas expertise. Argus LPG Vice-president Nick Black was fortunate to recently interview Arahata about his many years of experience.

Can you tell us how you first got into the LPG industry?

I graduated from Rikkio University in Tokyo and joined a firm called Bridgestone Liquefied Gas (now part of Eneos Globe) in 1972. Bridgestone was a pioneering LP Gas importer to Japan, owning a 16,000t refrigerated LP Gas vessel, the Bridgestone Maru — the world’s first ocean-going LP Gas vessel. The company’s involvement in LP Gas is interesting. Bridgestone sent Dr Yamamoto, an engineer, on a mission to the US to study the technology regarding storage and transportation of refrigerated liquefied gas (both LP Gas and LNG) in 1955. Bridgestone subsequently built its vessel in 1961 and an LP Gas import terminal Mr Nick Black, VP LPG of Argus Media

in Kawasaki. I joined Bridgestone as an engineer and helped develop a burner system for propane and butane. In 1973 I also went to US to study the various uses of LP Gas. One of my mentors, when I was a junior staff member, was Mr Y. Goh who later helped Stewart Kean establish the World LPG Forum.

Why did LP Gas become so popular in Japan?

Before LP Gas became popular, most of the Japanese used charcoal and firewood. In 1956, LP Gas demand in Japan was just 46,000 t/yr. But by 1960, demand had grown to 433,000 t/yr. LPG consumption per capita was just 4.6kg in 1960 — and is now around 128kg per capita. So about 50 years ago, the Japanese LP Gas market could be defined as an “Early-Stage LP Gas Market” according to WLPGA guidelines. The development of the Japanese economy is one key reason why LP Gas demand increased — as primary energy needs grew. But pioneering efforts by firms to develop the LP Gas market were also crucial, including educating potential consumers about the fuel. The industry had to develop the basic appliances and the equipment for LP Gas, which in case of Japan included equipment for Autogas and light industrial use. The petrochemical market was another target.

How did Japan secure the LP Gas supply chain?

Japan’s LP Gas supply chain consists of LP Gas ocean-going vessels, import terminals, pressurised coastal vessels, pressurised secondary terminals, tank tracks through to filling stations, delivery trucks and ultimately cylinders. We call the supply chain the “mobile pipeline” and the industry aims to ensure the chain should not be broken at any time and remain secure. We also explored new LP Gas supply sources to ensure supply diversity. Then as an industry we have worked hard to secure safety measures, codes and procedures. We have also worked hard to educate consumers. Securing good quality LP Gas has also been vital to the industry’s efforts. In the beginning, people thought that the higher the pressure of LP Gas was in a cylinder, the better the quality. But what really happened was that first ethane vaporised and then the pressure tended to quickly reduce, leaving residue in the cylinders. So maintaining the good and consistent quality of LP Gas was very important to help develop the LP Gas market. It was difficult to ask the manufactures to develop the innovative applications and appliances.

What market came first in Japan?

The Japanese LP Gas market was developed first primarily for cooking to replace traditional fuels like charcoal and firewood. Japanese housewives quickly understood how convenient LP Gas was for cooking. Retail fuel outlets started dealing with LP Gas cylinders in addition to charcoal and firewood. Those traditional fuels were replaced by LP Gas. Most of the fuel shops became LP Gas shops. The change in cooking fuel in turn led to a change in cooking stoves. This brought a change to the Japanese kitchen, which became modern. And when the kitchen changed, the Japanese life style and houses also became modern.

What was the Japanese market like before the start of imports?

Before LP Gas imports started, LP Gas was in domestic refineries and refineries only sold LP Gas to the market by cylinder. The quality of LP Gas was not very good. Some liquid remained in the cylinders without vaporised. The colour of the flame was orange. But when imports began, the situation changed dramatically. The imported LP Gas was not, as with refinery LP Gas, a propane-butane mixture. The imported commercial propane with more 90pc propane content became popular — when it burned, the colour of the flame was blue. This improved the image of LP Gas. But the importers had the challenge of how to sell butane, because suppliers of LP Gas asked Japanese importers to buy propane and butane together at the ratio of production at the processing plants. So Japanese marketers explored the butane market looking for use in the petrochemical, taxi and industrial sectors. LP Gas in Japan is still used in this way: propane is for domestic and commercial uses and butane is for petrochemical, taxi and industrial uses.

When was the Japan LP Gas Association formed, and did it enjoy industry support?

The Japan LP Gas importer and producer conference, which is now organised by the Japan LP Gas Association, was established in 1963 — and importers and producers used to meet regularly, sometimes on a monthly basis. The Japan LP Gas Association lobbies the government and the policy makers. Over the last ten years, its most remarkable contribution to the industry has been to secure the positioning of LP Gas in government policy as a source of gas energy, like LNG.

Over your long career what do you remember as the key moments of change for LP Gas, for example the coming of Saudi long-haul exports?

When I joined Bridgestone, LP Gas sourced from Kuwait was supplied by BP. The Fob prices were quoted based on the U.S Gulf netback. After the first oil crises, the operating companies were nationalised in the Middle East countries. In 1962 the Cif Japan price of LP Gas was about US$40/t. In 1972 the Cif Japan price was about $32/t. But after nationalisation, the CIF Japan price rose to over $120/t. In 1979, Petromin took over Saudi LP Gas marketing from the partners of Aramco and started LP Gas D-D contracts and introduced a monthly Government Established Price (GEP) followed by the introduction of a “Trigger Clause” into the D-D contract in 1983. Saudi firm Samarec took over in Jauary 1989 with a new GEP formula, then its own Samarec price. Finally the Saudi monthly Contract Price was introduced in 1994 and has remained since then as the key Middle Eastern LP Gas selling price formula. Japan began a mandatory stockpiling programme in 1981, whereby Japanese importers were required to set-aside LP Gas volumes as a mandatory strategic stockpile in their terminals. Another big change came in 1988, when Indonesia started LP Gas exports to Japanese companies. To realize this project, Japanese firms formed a consortium.

And now Japanese importers face new business circumstances?

The long-haul waterborne trading of LP Gas is changing by the arrival of US LP Gas exports from shale gas development. This is a key moment. Japanese LP Gas importers now have the option to buy LP Gas from US or Middle East suppliers. The buyers have opportunities to diversify supply sources and reduce the geo-political risks of particular supply sources. But I think that the price of LP Gas has now become too much expensive as a fuel. It must be affordable to the people who would like to use it. The 2011 tsunami and earthquake that hit Japan has also been also a key moment. After the disaster LP Gas was reaffirmed as an easily distributable and vital source of energy. LP Gas saved the lives of many refugees who escaped from the disaster. The taxis fuelled by LP Gas transported passengers as well as relief supplies — while the vehicles fuelled by gasoline or diesel had to queue up for hours to refuel. The profile and standing of LP Gas in the Japanese government as a result improved significantly.

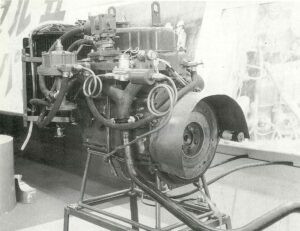

LPG vehicle 1963 LPG carburetors 1962 kit Autogas tanks in boot 1962 Carburetor from the US The Bridgestone Maru

The Autogas industry has a long history in Japan. How did it first start and what have been its major successes?

Our Autogas industry began with importing of LP Gas carburetors from the US in the early 1960s. The Japanese engineers developed and modified carburettors for the taxi use. The taxi companies realized the advantages of Autogas over gasoline: the Autogas octane number was high, the prices of Autogas were competitive with conventional fuel prices and the life time of engine oil lasted longer. Furthermore, the pump price of Autogas was kept at about 60pc of gasoline prices. Carburetor from the US Japanese car manufacturers Toyota and Nissan started supplying factory-fitted Autogas vehicles to the taxi industry. Currently about 80pc of all taxies are fuelled by Autogas. And Mazda supplies Autogas OEM vehicles to the driving schools in Japan. There used to be problems with the quality of Autogas which caused various engine troubles. But the LP Gas industry co-operated with the Autogas vehicle manufacturers to successfully resolve the problems.

From left to right: Autogas tanks in boot 1962, LPG carburetors 1962 kit, LPG vehicle 1963

You have been actively involved in the World LP Gas Association for many years. Do you think it has changed a lot over the years? If so, what have been the major changes?

Yes, there have been many changes. The network projects of such subsidiary WLPGA bodies as GAIN and GLOTEC have become more active — and the chances through which the individual members can actively participate have increased. It seems to me that the issues which the WLPGA has taken up are now well-balanced between global and regional concerns — and between emerging and developed markets. There are many recent examples of this kind of balance, such as the Cooking for life initiative, Guidelines for the Development of Sustainable LP Gas Markets and other Guidelines and Document (GHP, micro-CHP) compilations and HNS issue. The communication on the internet between members has also improved.

Do you have any favourite memories from all the WLPGA Forums you have attended?

Each WLPGA Forum has given me many good memories and a sense of togetherness of the global LP Gas families from the various regions, based on good communications on the WLPGA platform. Two forums particularly stand out for me: The WLPGA Forum Chicago in 2006 and the Bali forum in Bali in 2012. At Bali, the 25th WLPGA Forum. I helped put Mr.Goh’s contributions to the WLPG Forum in the silver anniversary book prepared for the event.

Does LP Gas have a future in Japan?

Yes, it has. But we must realise that nothing will happen unless we innovate our LP Gas business like our LP Gas industry did in 1960s and in 1970s. The Japanese population will reduce and energy saving technologies will improve. Those trends tell us the demand for energy will decrease. In other words, competition among the energies, electricity, city gas and LP Gas, will become more severe. So the price of LP Gas at the consumers must be competitive.

What are your views about the growing importance of US LP Gas exports to the Asia-Pacific? Do you think that they will eventually replace Middle East supply?

US LP Gas exports will certainly become much more important. But it is unlikely that US LP Gas will totally replace Middle East LPG. I think a 40pc penetration level will be likely in case of Japan and South Korea.